The Knotty Origins of Encoding

When I was younger, anytime someone mentioned data, I pictured a stream of 1s and 0s like the Matrix when Neo figures out he’s the One. Later, once I became a bit more data-literate, my brain swapped out binary code for rectangles (bars) or neatly arranged circles (dot plots). These shapes weren’t just pretty pictures; they were systems of encoding. A shared language, built to make information visible and understandable.

But data has existed long before spreadsheets, charts, or even computers. It existed in knots.

- The single knot.

- The long knot.

- The figure-eight knot.

- And the most important knot of all the historical ones we’re about to untangle today.

Welcome to Data in the Wild

This is the series where we highlight everyday examples of data viz in action, analog, ambient, and often overlooked. I’m always glad to speak to a like-minded audience who doesn’t just ask, “How are you feeling today?” but follows up with, “On a scale of 1 to 10?”

This week, we’re talking about quipus (also spelled khipus), a system of knotted strings used by ancient Andean cultures to store and transmit information. That’s right: data visualization made of yarn.

Untying the Knot

“Quipu” literally means “knot” in Quechua. And while they might look like decorative macramé at first glance, don’t be fooled, these weren’t for show. They were sophisticated data tools used by the Inca Empire (and earlier Andean societies) to record everything from taxes and census data to calendars and genealogy.

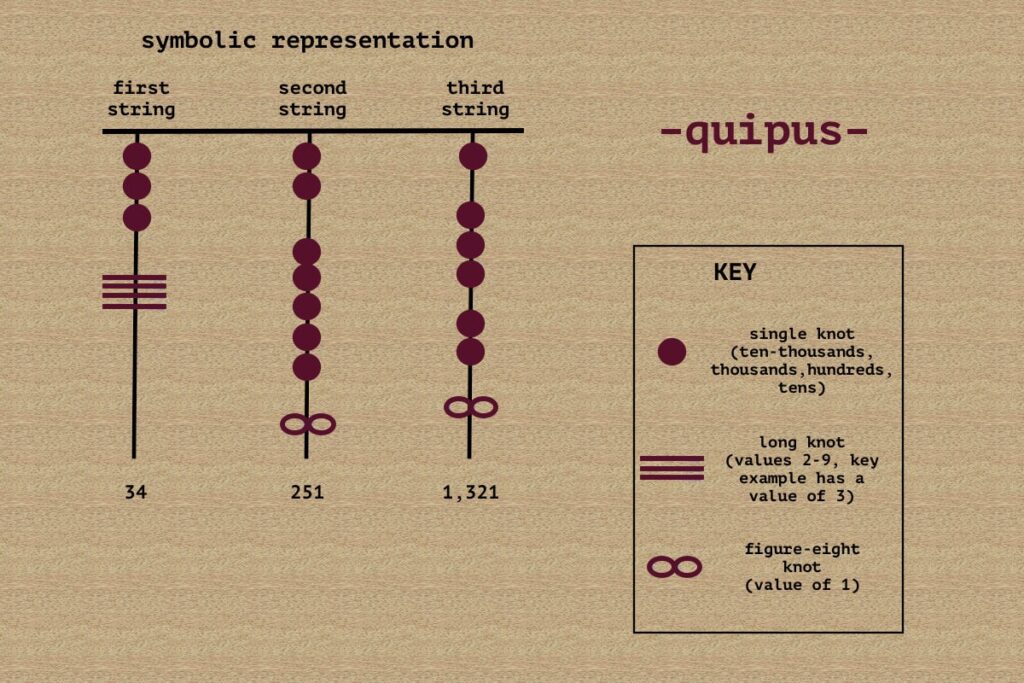

Each knot had meaning:

- Single knots represented powers of ten: tens, hundreds, thousands.

- Long knots represented numbers two through nine, based on the number of loops.

- The figure-eight knot was the number one.

With no written alphabet, the Inca developed a tactile information system, read with the fingers rather than the eyes. Think of it as a wearable spreadsheet made of cotton or camelid fiber, lightweight and durable, perfect for chasquis (Incan messengers) running across rugged mountain terrain with government intel.

Even more mind-blowing? Quipus predate the Inca; some examples go back as far as 2600 BCE. When the Inca conquered new regions, they would send in quipucamayocs (record keepers) to count everything: streams, fields, mines, crops, livestock, and people, even breaking it down by gender. All of that information was tied into a quipu and brought back to Cusco to help govern the newly acquired territory.

- It was a census.

- It was an infrastructure report.

- It was also a subtle and brilliant act of dominance. After all, what better way to claim ownership of a place than to have all the data on it?

A Lesson From History

From a data viz perspective, quipus are a masterclass in encoding. They used structure, hierarchy, materiality, and color, the same principles we use today in dashboard design or information architecture.

So next time you see a knotted friendship bracelet, an art installation made of string, or even a tangled set of earphones, pause for a moment. You might be looking at a distant cousin of one of the world’s oldest data systems.

See you next time when we uncover more data… in the wild.

Data in the wild #16: Can You Share Your Location

In this edition of Data in the Wild, I explore what it really means to “share your location.” From GPS and Wi-Fi to ship tracking and TfL demand modelling, this piece unpacks how geolocation works, where it shows up in everyday life, and what we can build when movement becomes data.

Data in the wild #15: The Data Behind Fireworks

Fireworks don’t just light up the sky they’re shaped by data. From wind modelling to sound limits, invisible thresholds decide what counts as “safe fun.” This Data in the Wild piece explores how decibels, maths, and regulation quietly shape one of our most beloved celebrations.

Data in the wild #14: Light, Lasers & LIDAR

Imagine mapping the world using light. That’s exactly what LiDAR does. It fires laser pulses that bounce off objects and return to a sensor, calculating distances with GCSE-level physics. Repeating this millions of times creates point clouds detailed 3D maps. From mapping cities to powering self-driving cars, LiDAR reveals the invisible.