This is the seventh article in my Visualisation Insights series. The purpose of this series is to provide readers with unique insights into the field of visualisation from the different perspectives of those in the roles of designer, practitioner, academic, blogger, journalist and all sorts of other visual thinkers. My aim is to bring together these interviews to create a greater understanding and appreciation of the challenges, approaches and solutions emerging from these people – the visualisation world’s cast and crew.

This article is based on an interview I held with Brian Derry, the Executive Director of Information Services at the NHS Information Centre, based in Leeds (UK).

I first came across Brian when I discovered an article in the Health Services Journal (subscription required) entitled ‘Demystifying data’ in which he was quoted about the importance of the visual display of data. His opening statement that “3d charts are the first refuge of scoundrels” was music to my ears.

Quite apart from this appealing standpoint, his role as custodian of so much valuable statistical information relating to health and care matters makes him one of the most important information professionals in the UK so I was delighted when he invited me over to meet him for a chat about his role, the work of the Information Centre and the importance of clearly communicated data.

![]()

Brian is a chartered statistician and chartered IT professional. Having studied Statistics at degree level, he began his working life as a Government statistician for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF, now known as DEFRA) working on significant analytical projects such as the National Household Survey.

After leaving MAFF he moved on to the Home Office, taking up a key role with the remit of trying to develop information products that help explain and improve the management of prison parole, a particularly complex system which has many flows, branches, stocks, decisions points and feedback loops.

A whole new level of complexity faced him when he took up the role of Head of Performance Analysis at the Department of Health in the early 1990s. This commenced his distinguished career in or around the National Health Service (NHS) which has encompassed a succession of senior and director-level informatics posts at the Leeds Health Authority, the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and NHS Connecting for Health.

His most recent career advancement took him to the position of Executive Director of Information Services at the NHS Information Centre in Leeds. He recently completed his term of office as chair of the National Council of The Association for Informatics Professionals in Health and Social Care (ASSIST) and is currently the Chair of the British Computer Society health informatics Professional Development Board.

![]()

The Information Centre was created in April 2005 as a result of the bringing together of a range of historically discrete information agencies, as well as key parts of the Department of Health and the Information Authority.

It is responsible for running major information collections and statistical publications relating to a broad spectrum of health and social care service topics such as measures of care quality, hospital activity, prescribing, primary and community care, mental health, adult social services, population health, lifestyle surveys, alcohol, obesity, the NHS workforce and NHS estate.

The centre employs around 500 people, of which about 70% are based in Leeds and the remainder based in Southport. The staff in the Leeds office comprise a diverse range of skills and expertise with a mixture of IT people (managing sophisticated systems, data warehousing, survey processes), statistical analysts, business analysts, information governance specialists, HR people,communication professionals, project and programme managers, and health care specialists. The Southport ‘Central Register’ office has the unfortunate label of ‘National Back Office’ (“a terrible name”, as Brian suggests) but is recognised as providing an incredibly important service dealing with the management of the national register of NHS patients and their NHS numbers (the national unique patient identifier) and therefore has access to a huge amount of vital data.

A large proportion of the Information Centre’s workload involves producing official statistics for central government to help develop and account for health policy. However, as Brian points out, since its inception, the organisation is moving more and more towards a focus on what is most useful for the NHS and Local Government in order to help improve their services. This is a hugely positive trend.

Having recently been the subject of review, and given the political climate under the new Government, it is great news to hear that the Information Centre continues to be recognised as a vital national repository of information with the review concluding it provided a valuable service. It will now become a non-departmental public body operating at arm’s-length from the Department of Health.

The Information Centre is now looking to enhance its service across several key areas with particular emphasis on facilitating an increased centralised collection of information, continuing to increase the range of information useful for patients and the public, especially around the quality of service measures, and aspiring to sustain the quality and quantity of provision but with greater efficiency (in terms of both cost and access). As Brian points out:

“Information is not a free good so there is an increasing need to make best use of it, making it work in combination rather in isolation and joining up a single cohesive story.”

This creates greater value and impact.

![]()

At an early stage in his career, Brian was aware that much of the output of Government statistical work was impenetrable, produced by civil servants for civil servants and not presented in ways that would make it meaningful to everyday people. His keen interest in identifying effective visual methods for information displays can be traced back to these early experiences.

He is careful, though, to recognise the acute complexities of many of the service environments and organisational systems he has worked in, especially in some of his earlier roles where the people making key judgments were not particularly technical or information-minded people. No system is more complex than the NHS and the challenges faced by information professionals are becoming greater as the desire for improving the understanding of quality of care grows.

“Trying to explain the NHS in numbers is hard. How do you effectively describe how good a service may be?”

Brian points to a specific difficulty with how you effectively present mortality rates, where you are trying to convey notions of wide variation and constant changes in trends in an accessible way:

“We now live in a world where patient choice is terribly important, with people choosing how and where to receive care. But choice without information is no choice at all.”

The key challenge is about communicating such information to people in ways that reduces the complexity and enhances their ability to choose.

![]()

Continuing the issue of the civil servants being responsible for communicating statistical work, Brian points to the specific demands involved in dealing with non-specialists in the NHS context. He refers to his past experience working with senior NHS managers where the people he dealt with were typically highly intelligent, in key positions but had no statistical training and were not always particularly numerate. Yet these people operate in an environment where everything is judged through complex indicators and so this pressure in combination with a lack of expertise creates a culture focused on dissecting short term differences in numbers without fully considering the bigger picture.

As a service which is generally renowned as being obsessed with chasing targets, in the NHS data can be subjected to scrutiny at such a micro level of detail, and observed within a random distribution, that it creates a narrative fallacy:

“If you present a set of numbers, people will spend hours trying to explain reasons for those numbers. But too many fail to understand variation very well – you need a run of numbers to include a context. You cannot establish any idea of performance history when you only see two data points in isolation.”

So given this strong culture, how do professionals in the Information Centre deal with clinical colleagues who may commission or consume information projects? How do they manage to endorse their own expertise, particularly in circumstances where there is a client wishing to dictate matters?

Brian describes how when dealing with colleagues they approach the engagement as if it were a standard consultancy project with a focus on clearly identifying a separation between wants and needs, and establishing the specific problem that is trying to be solved. This is about professionally managing the relationship ensuring there is respect for the mutual areas of expertise.

“We are open to challenge, and should be too, but we can rightly say that we may know of ways of doing this better, so it depends on the opportunity for dialogue.”

Situations naturally get most anxious when analysis is being presented on information which directly relates to clinical colleagues, so it is about building trust and ensuring they fully understand the data and the analytical treatment on which they may be judged.

“There can be nothing worse than being judged on information you didn’t know existed.”

A process challenge facing the Information Centre, and indeed any large public sector body responsible for information management, concerns the need effectively balance the production and analysis of information. So much time can be absorbed by the gathering, handling and statistical analysis of data to the detriment of the opportunity to derive meaning from the information results. This can be a symptom of over-accountability, a situation where the recording and production of information is relentlessly ‘feeding the beast’ that is a public service organisation and its myriad stakeholders. The cost of capturing and processing data is huge and so it is important to be reminded that information should be seen as a by-product of activity, not the activity itself.

“The information tail should not wag the service dog”, remarks Brian.

![]()

One of the most challenging components of NHS performance concerns the assessment of quality of care and a key dimension of quality is the patient experience. But how do you capture the type of data you need to monitor patient perception of the care they have received?

A structured source of evidence comes from sites like ‘I want great care’ are providing important channels for capturing and analysing information about patient experiences, their views on the quality of care they have received, perceptions of GP performance etc. On top of this, excellent data is gathered via large number of surveys which record patient attitudes about the care they have received.

A significant growth area in the information management and statistical world is sentiment analysis. The catalyst has been the ubiquity of social networking services like Twitter and Facebook which create incredible volumes of accessible qualitative data. The challenge is to identify the most effective uses, algorithms and means of mining this data from a health service ‘attitudes’ perspective.

Brian notes that a key barrier to the maturity of analysis around this matter concerns access to computer technologies: the heaviest use of health and social care is among the very young and the elderly. Additionally, health is typically linked to deprivation so patients from lower social backgrounds are also restricted from having their voices heard through some of these contemporary, technologically driven channels. This represents a significant problem for securing a comprehensive and efficient picture of perceptions around this quality of care. Identifying an effective solution to resolve this particularly complex and elusive challenge is a priority for information professionals across the NHS.

![]()

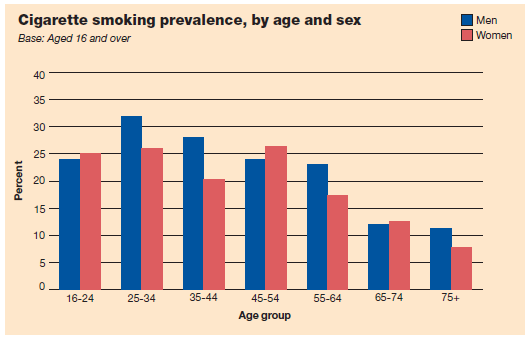

I asked Brian about his views around the visualisation and communication side of his organisation’s work. In terms of the challenge in explaining statistical information to the public, he points a finger of blame towards media’s role in failing to promote clear communication.

“Large portions of the media are largely more concerned with graphic design over content which can confuse viewers and readers, missing the message completely.

The only purpose of a chart is to convey message accurately and clearly but most of the information you see in the media fails these basic tests. 3D charts are a particular bug bear. Whilst they are technically clever pieces of design, they fail to communicate accurately and sometimes this is intentional. Conveying genuine meaningful information is our priority, not getting distracted by graphic design.”

Brian also believes the media seem to amplify a society-wide shortcoming with regards to numeracy. He observes how many people struggle with the nuances around statistical concepts such as percentages, percentage changes and percentage point changes, all particularly common devices used to support the presentation of news items.

People are also becoming less patient, there is a society wide culture that demands information, immediately and without having had to plough through masses of detail. People don’t want to have to work for information, so it should work for them. This makes the challenge of presentation so critical – if you cannot convey your message instantly, forget it.

On a broader basis, there is failure to keep things simple. Brian cites a quote attributed to the French mathematician Blaise Pascal who said something to the effect of

“I am sorry I have had to write you such a long letter, but I did not have time to write you a short one.”

It is the same with charts – I’ve not had time to do a simple chart so here’s a complex one. However, there is a balance to be struck and sometimes there is such a drive to “simplify, simplify, simplify” that sometimes the key content is abandoned in doing so.

![]()

I asked Brian about the advice or guidance provided to his analysts about approaching the visualisation stage of their work. Many of the professional statisticians belong to the Government Statistics Service which spans all government departments and this body has clear standards and principles to follow about the presentation of data. Beyond the specifics of these standards there is a general house rule which promotes good statistical practice to be about focusing on the content first, design second. When it comes to design, analysts need to constantly ask themselves “will this accurately convey the message?”

Brian also draws a key distinction between the activity of analysing and communicating data and the difference each entails with regards to design:

“It is really important you are clear about what you are trying to do. Are you describing a set process or system? Are you answering a question about a hypothesis? Or are you using it to make a particular point?”

Despite the presence of clear house rules around statistical and presentation practices, the Information Centre’s analysts are actively encouraged to ensure they are taking full advantage of latest technological developments and contemporary thinking. Indeed this is an area of business they invest a lot of time and effort in. By way of example, to support this culture of ongoing development, a member of staff is currently doing a PhD around statistics at the University of Leeds and a strategic relationship has been formed with the same institution. This provides mutual access to key seminars and events, Information Centre staff routinely teach on some undergraduate courses and they also collaborate in many areas of research activity.

The software used by staff lists many of the typical tools you would expect within such an information-rich environment. They use Microsoft Office products, SQL server databases, SAS analytical tools, and various GIS applications – as Brian observes “health is very concerned with patterns of geography”. They also have access to extremely large data warehouses operated by commercial partner organisations such as BT, for example the ‘Secondary Users Service’ which takes continuous records of patient care amounting to millions of lines of data.

There are some concerns around the extensive use of Excel and Access. They are still popular tools but are considered difficult to control at scale and this can lead to errors concerning issues like cell linkage inconsistencies and ‘cut and paste’ mistakes, particularly when utilised in shared processes.

The general approach in the Information Centre is to standardise methodologies, creating a sophisticated environment of working that is portable and generic and not overly reliant on a single technology to achieve everything. To support this approach they have begun moving more towards a data management environment built around SAS, with enables shared references, macros, access to data sources, is considered much more efficient and, importantly, reduces the risk of errors.

![]()

One of the significant developments within information management in recent years has been the emergence of the open data movement. I asked Brian how he viewed this in the context of NHS-related information – is it a positive development, does it pose a risk or opportunity, does it create added pressure/demands on his organisation?

Emphatically he thought it was a positive development and believed a certain amount of risk-taking should be encouraged, but he was mindful of certain challenges that accompany this environment.

“We need to move away from the state control – the public have come along way so the more information that is available, and in a form for anyone to use it, the better.”

The adverse risks he recognises concern issues of understanding, appreciating that with certain information contexts results can be misinterpreted, so supporting features like reference files and meta-data are vital.

The boundaries of transparency are also changing and the classic public service view of confidentiality is slowly diminishing, which is very healthy. For example, clinicians are now routinely named in certain packages of analysis – that would never have been the case not so long ago but reveals a far greater willingness to embrace transparency. It is still important, however, to be very careful in many circumstances when patient confidentiality is concerned. Issues of potential identification can crop up within subjects that involve small numbers, particularly when presented in a geographical context. Whilst the analysis may not immediately reveal individuals it does open up the possibility for people to triangulate data and arrive at an identity.

![]()

As a public body it is more important than ever to be able demonstrate effectiveness and value for money. I asked Brian how success is judged in the Information Centre?

Much of the immediately available evidence comes through standard web analytics with extensive information available on typical measures around visitors, pages visits, which datasets viewed and downloaded. They also have activity from registered users via a service on the Information Centre website called ‘My IC‘. This helps to collect information about what subjects users are most interested and provides a convenient channel for running survey campaigns across these regular customer groups.

Whilst having a fairly advanced understanding of the usage of registered users, the biggest gap surrounds the use of their information services by patients and the wider public. More and more data is getting out there, and there is good research about what is generally helpful to public, but it is still difficult to track how the information is being used to drive action or insight by these groups:

“We need to keep pushing to establish a great understanding of what it is you [the public] want, how do you want to use it, how could it be done better – a level of intelligence greater than can be derived from simply running surveys. This is a great challenge.”

Brian cites the ever increasing sophistication of people and their constantly changing behaviour and tastes around consuming information, driven by technology. In response, one of the more non-traditional methods employed to understand how people are engaging with the site and its services has been work such as that by City University using eye-tracking to identify the ergonomic factors around the web layout and design.

My final question was to ask Brian to project himself five years into the future and consider what will represent success for the Information Centre over that period.

“If a lot more of the information around the NHS was more readily available and was being used and understood, especially by the public. That would be a success. We will have also developed better measures for the quality of care. But overall, we will have succeeded if the Health system was beginning to use the information effectively to improve its services. Data is for information which is for improving public services.”

*************************

I’m extremely grateful to Brian for inviting me down to meet him for this interview and the energetic and informative discussion that ensued. I took a great deal out of this, unearthing more and more nuggets of wisdom every time I listened back to the audio recording. I wish him and his colleagues at the Information Centre all the very best for the future in their undertaking of this hugely valuable activity.