Happy New Year!!

Happy New Year 🎆

I don’t know about you, but one of my favourite traditions when entering the new year is fireworks. I’m not sure whose idea it was to colourfully bomb the sky to celebrate the passing of time, but whoever they were… they were correct.

London’s first official New Year’s Eve fireworks display took place in the year 2000, produced by Bob Geldof’s Ten Alps. An estimated three million pairs of eyeballs were glued to the spectacle. Since then, we’ve been locked in. And it’s not just London. From China to Dubai, New York to Sydney, fireworks have become a global language for celebration.

Which means, as we step into a new year, I have to ask the obvious Data in the Wild question:

WHAT IS THE DATA BEHIND FIREWORKS??

Welcome to Data in the Wild

Welcome to a new year and a new edition of Data in the Wild the series where I investigate how data is formed, measured, and quietly used to influence the world around us. And there are few better places to start the year than fireworks.

What does data have to do with fireworks?

As it turns out… quite a lot.

Fireworks displays don’t just “happen.” Behind every explosion of colour is a web of calculations, models, thresholds, and limits. Weather data, especially wind direction and strength, plays a huge role. When a firework is launched, what’s really happening is a controlled chemical reaction inside a shell, fired at a specific angle and height.

Once it explodes, gravity takes over. Debris, smoke, and fallout return to earth. For large-scale displays like New Year’s Eve in central London, planners model where that debris might land, how smoke will move, and how emissions could affect the surrounding environment and the people living there.

But while wind, trajectories, and carbon output matter, the variable I want to focus on is an invisible one and arguably the most important of all.

Sound.

Measuring the invisible: how loud is loud?

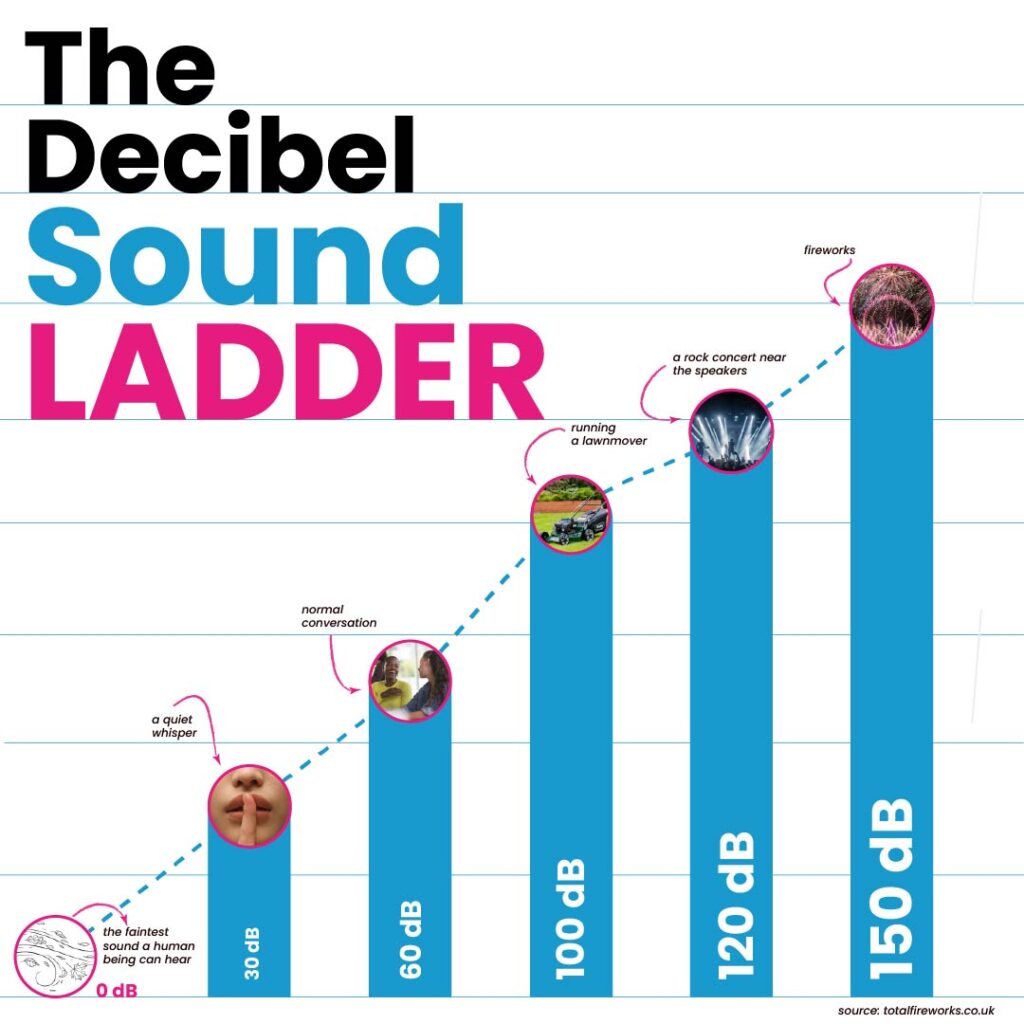

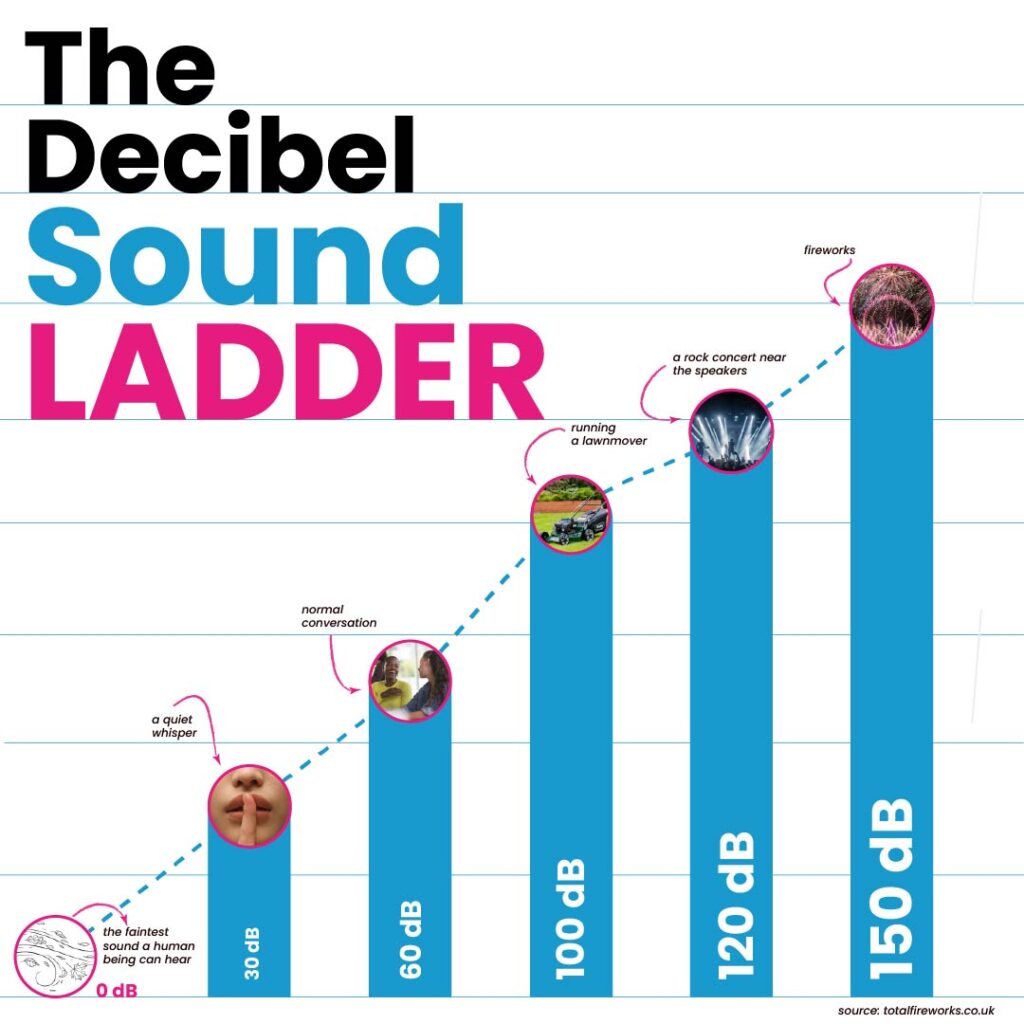

Sound is measured in decibels (dB) using sound sensors that capture changes in air pressure. These measurements give us benchmarks for what’s comfortable, uncomfortable, and outright dangerous.

Here’s a quick reference:

- 0 dB – The faintest sound a human ear can detect

- 30 dB – A quiet whisper

- 60 dB – Normal conversation

- 100 dB – A running lawnmower

- 120 dB – A rock concert near the speakers (the point where pain and hearing damage can begin)

- 150–175 dB – The range of many fireworks at source

Generally speaking, prolonged exposure to sounds below 70 dB is considered safe. Above that, exposure time matters. Short bursts may be fine, but as sound levels increase, the risk of permanent hearing damage rises rapidly.

And this is where things get interesting.

Common Sense Media

Measuring the invisible: how loud is loud?

Sound is measured in decibels (dB) using sound sensors that capture changes in air pressure. These measurements give us benchmarks for what’s comfortable, uncomfortable, and outright dangerous.

Here’s a quick reference:

- 0 dB – The faintest sound a human ear can detect

- 30 dB – A quiet whisper

- 60 dB – Normal conversation

- 100 dB – A running lawnmower

- 120 dB – A rock concert near the speakers (the point where pain and hearing damage can begin)

- 150–175 dB – The range of many fireworks at source

Generally speaking, prolonged exposure to sounds below 70 dB is considered safe. Above that, exposure time matters. Short bursts may be fine, but as sound levels increase, the risk of permanent hearing damage rises rapidly.

And this is where things get interesting.

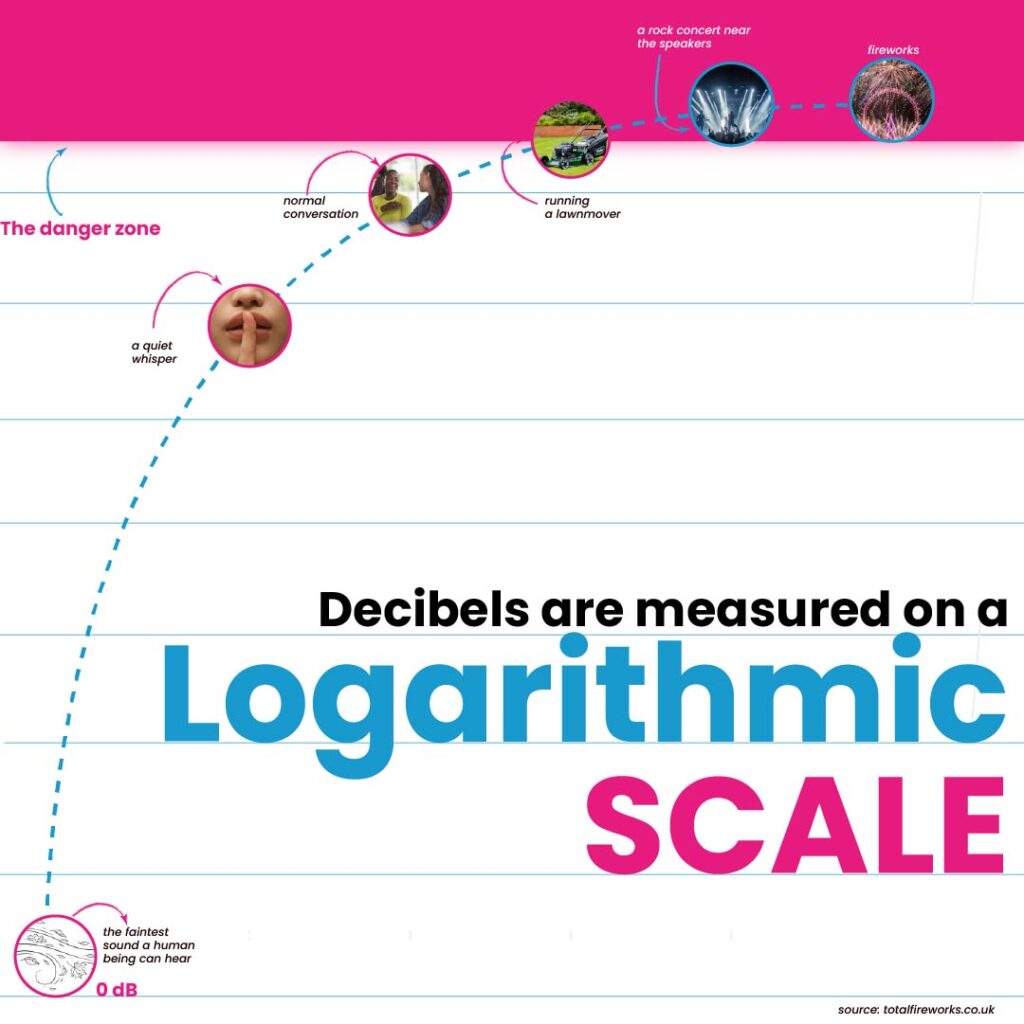

Why a decibel chart can lie to you

If we were to chart these sounds on a simple bar chart, it might look like fireworks are just “a bit louder” than a concert or a siren.

But that chart would be misleading.

Decibels are measured on a logarithmic scale, not a linear one. This means that every increase of 10 dB represents roughly twice the perceived loudness.

So 120 dB isn’t just slightly louder than 110 dB it feels dramatically louder. Fire truck sirens often sit between 110 and 120 dB. Fireworks, at 150 dB or more, aren’t a small step beyond that. They’re operating in a completely different danger zone.

If fire sirens stuck in traffic are enough to give me a headache, fireworks clearly aren’t something our ears should take lightly.

How Data informs policy

This is why governments step in.

In the UK, consumer fireworks are legally capped at 120 dB, and there are strict rules about when fireworks can be used throughout the year. Not because fireworks aren’t beautiful but because sound isn’t just an experience, it’s a biological stressor.

Data doesn’t just measure noise here.

It decides who gets to make noise, how close, how often, and when.

It shapes policy, safety guidance, and cultural norms around celebration. It draws a line between “fun” and “harm”…even when that line is invisible.

Data in the Wild

Fireworks are a perfect example of Data in the Wild. Most of us look up at the sky and see colour, spectacle, and celebration. But hidden beneath that moment are thresholds, models, and measurements quietly working to keep that fun within acceptable limits.

So next time you’re watching colourful explosions ripple across the night sky, ask yourself:

Where do these fireworks sit on the scale?

Who decided that was safe?

And what invisible data is shaping the way we celebrate?

Because sometimes, the most powerful data isn’t what we see

it’s what we hear.

Data in the wild #16: Can You Share Your Location

In this edition of Data in the Wild, I explore what it really means to “share your location.” From GPS and Wi-Fi to ship tracking and TfL demand modelling, this piece unpacks how geolocation works, where it shows up in everyday life, and what we can build when movement becomes data.

Data in the wild #15: The Data Behind Fireworks

Fireworks don’t just light up the sky they’re shaped by data. From wind modelling to sound limits, invisible thresholds decide what counts as “safe fun.” This Data in the Wild piece explores how decibels, maths, and regulation quietly shape one of our most beloved celebrations.

Data in the wild #14: Light, Lasers & LIDAR

Imagine mapping the world using light. That’s exactly what LiDAR does. It fires laser pulses that bounce off objects and return to a sensor, calculating distances with GCSE-level physics. Repeating this millions of times creates point clouds detailed 3D maps. From mapping cities to powering self-driving cars, LiDAR reveals the invisible.