In order to sprinkle some star dust into the contents of my book I’ve been doing a few interviews with various professionals from data visualisation and related fields. These people span the spectrum of industries, backgrounds, roles and perspectives. I’ve only scratched the surface with those I have interviewed so far, there’s a long wish list of other people who I haven’t approached yet but will be doing so. My aim is to publish a new interview each week through to the publication of my book around April/May 2016 so look out for updates every Thursday!

I gave each interviewee a selection of questions from which to choose six to respond. This latest interview is with John Nelson, Director of Visualization at IDV Solutions. Thank you, John!

Q1 | When you begin working on a visualisation task/project, typically, what is the first thing you do?

A1 | I kick it over into a rough picture as soon as possible. When I can see something then I am able to ask better questions of it –then the what-about-this iterations begin. I try to look at the same data in as many different dimensions as possible. For example, if I have a spreadsheet of bird sighting locations and times, first, I like to see where they happen, previewing it in some mapping software. I’ll also look for patterns in the timing of the phenomenon, usually using a pivot table in a spreadsheet. The real magic happens when a pattern reveals itself only when seen in both dimensions at the same time.

Q2 | With deadlines looming, as you head towards the end of a task/project, how do you determine when something is ‘complete’? What judgment do you make to decide to stop making changes?

A2 | I have the benefit of, for the most part, making visualizations for fun, as time permits (my official capacity revolves around software user experience and information architecture). As such, I’m generally the only one who has to decide if when something is done, and there really are no looming deadlines, other than my impatience to share the results on the web. When I step back and think, ‘Ok, they are really going to like this’ then I know I’m in an alright spot. Invariably I have a spelling mistake in there though, that a reader will point out early on, so there is usually one last unfortunate revision before I am actually done.

Q3 | How do you mitigate the risk of drifting towards content creep (eg. trying to include more dimensions of a story or analysis than is necessary) and/or feature creep (eg. too many functions of interactivity)?

A3 | Once I heard a quote by Billy Wilder, on effective storytelling, where he said something like “…give them two and two, and let them add it up.” The most exciting dialogues I’ve had around visualizations was when I just show the data with no commentary or explanation. Visualization designers are almost never experts in the topic we design for; I learn the most when I like to stick to the showing and then listen. Also, this way you engage visualization participants, rather than pitch to visualization readers.

Q4 | At the start of a design process we are often consumed by different ideas and mental concepts about what a project ‘could’ look like. How do you maintain the discipline to recognise when a concept is not fit for purpose (for the data, analysis or subject you are ultimately pursuing)?

A4 | I have the lazy benefit of being a specialist. If the data isn’t spatial, it is unlikely I’ll dig into it for a visualization. Most of my head-scratching comes when trying to determine what complimentary graphics to include or not to include. I have had some projects where I found the analytical method I was walking down yielded beautiful, though misleading, visuals. Then I had to throw it away and start over (see “False Start” section)

Q5 | Whilst there is a great deal of science underpinning the use of colour in data visualisations, a lot can be achieved through applying common sense. What is the most practical advice you’ve read, heard or have for relative beginners in respect of their application of colour?

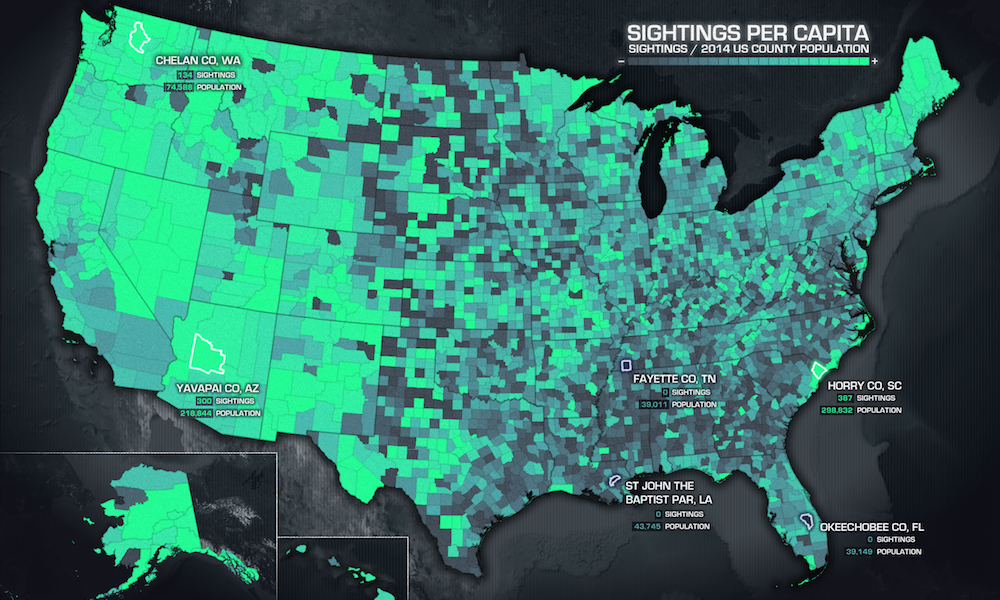

A5 | Too many colors! Keep the palette simple and clean. If the background is dark, use brightness to denote higher values; if the background is light, darker values. The phenomenon and the background lightness should oppose each other; contrast is the vehicle for magnitude.

Q6 | Presenting spatial data is a specialist discipline and one that involves a lot of different challenges to other types of charts and graphics. Not wishing to reduce this discipline to a diluted bullet point list but what would be 2/3 key pieces of advice – or pitfalls to avoid – you would offer folks facing this kind of challenge?

A6 | When making a choropleth map, chose your range breaks carefully. There is an elusive balance between choosing color ranges that respect the user and the integrity of the phenomenon, and in teasing out the story the phenomenon has to tell. That balance lies somewhere between mathematically dogmatic range breaks that communicate little and creative range breaks that propagandize. (see article “Telling the Truth“)

Most maps are now made with readily-available software that lowers the barrier to entry for many designers, and this is terrifically exciting to me. It does, however, also give me the opportunity to encourage more novice map-makers to avoid the defaults. Each factor should be an active choice by the designer, rather than automated passive acceptance (see “Avoid the Defaults” section)