I have written in the past about the way those of us active in the field operate within something of an artificial environment. It is unavoidable and not unique to data visualisation but when your day is spent networking and communicating ideas largely just with other captive members of the discipline you do so within a bit of a bubble. This means you potentially miss out on important perspectives of people who would be self-defined as casual, occasional consumers or maybe just newly interested in visualisation work.

Likewise, when your vocation involves creating or digesting a wide range of visualisation work every day you view work through the lens of a designer or critic. It is not easy to revert to a neutral or default perspective. Like any profession, you are somewhat cursed by knowledge.

This means that I am very fortunate to run training sessions that provide me with a window to access insights from more casual observers (*). I see how people interact and perceive many different data visualisation and infographic works, from instinctive evaluations and through to more forensic design judgments.

One of the most interesting observations has been the significant influence a project’s subject matter has on people’s reactions. Works that I might celebrate as being great examples often provoke divided opinion across a group and frequently the connection between the reader and the subject matter is cited as a key reason for indifference.

This has made me think about my own consuming of visualisation work. Projects that I might share or profile are usually exhibits of my appreciation of a design concept or technical solution but I rarely consider the appeal of the work from the perspective of its subject matter.

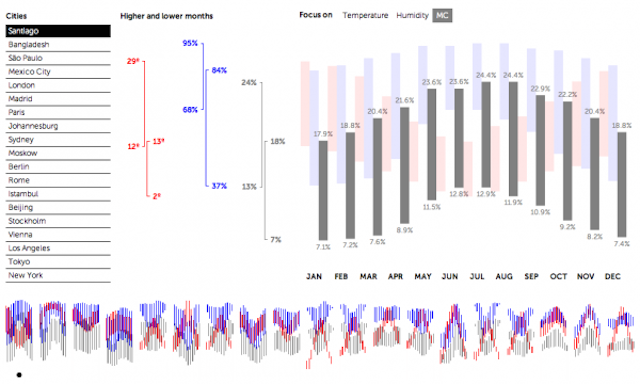

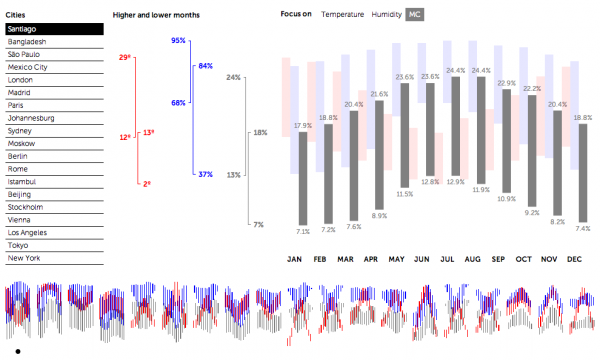

A few examples. Firstly, this visualisation from last year about changes in wood dimensions. Technically, I think it is a superb piece of work. Extremely well conceived and executed, I included it in my top 10 developments of the time. Yet, if you were to ask me if I’d actually taken the time to learn anything about the subject matter I would have to concede ‘no’. I frankly have little interest in the subject matter and, as much as I might try, I’m never quite going to connect with it on that level.

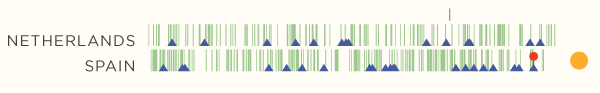

On the other side of the fence, I have previously expressed my great fondness for this work on football match stories by Michael Deal. I think it is a superb concept to visually encode the key activities within a game and, to me, it reveals fascinating stories of ebb and flow in each encounter. But I am also a huge football fan and would happily spend far too much of my time digesting anything and everything to do with the sport. I know others would not, indeed they would be repelled at the prospect. So, once again, irrespective of the quality of the idea and the final visual, this will only reach a certain audience.

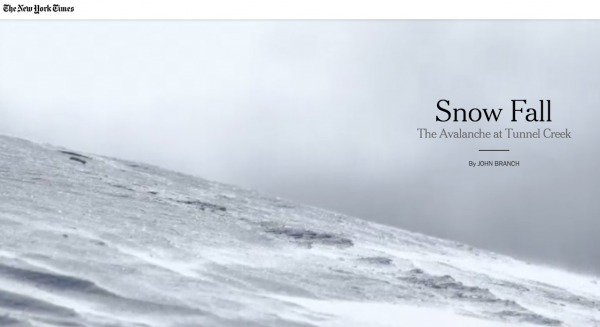

A final example: Snow Fall. (Not enough has been said about this, I know that’s what your thinking. Well here’s a little bit more analysis.) This isn’t an example of visualisation alone but as a form of contemporary digital storytelling was quickly picked up by and shared amongst this community.

The great swell of positive response to this project has been largely universal. But how many of us have actually read it all the way through? How many of us have actually read anything beyond the opening paragraph? I know very few who have – myself included – and yet we celebrate the work almost in terms of being a game-changer. That’s mainly because we readily judge it as a great artefact of story-telling design, rather than something we have read and been affected by it’s subject. (Incidentally, whilst I don’t necessarily agree with all the points made here this article is an interesting counter-perspective to the broad celebration of Snow Fall).

The point I’m making here is about appreciating limits of appeal. We can create the very best portrayal of data – elegant, attractive, interactive and different – and demonstrate attributes of effective design but we can never achieve perfection. We can never get everybody on board because there is always a subject matter involved and that will be something that ignites or dampens a reader’s desire to continue reading and discovering. We might work really, really hard to create something that achieves eyeballs on our work but soon the visual novelty will wear off for those who simply are not interested in the core topic.

The two key reminders for me:

- As ever, an appreciation of your intended reader is key: a realistic view of who you are and are not aiming a project at will frame your design decisions as well as define your judgment of whether it succeeded or not.

- Optimisation – doing our best within the context of what we can achieve – is a really important mindset to get into. You will never achieve 100% so don’t expect it and don’t suffer when you don’t reach it

(*) I am loathe to use terms like ‘normal’, ‘everyday’, ‘non-expert’ to categorise this cohort. There is no way to avoid sounding like a prat so hopefully you get what I mean by the clumsy descriptions I have used!